-

The Six of Calais & Ruth - 01/20/2023

-

SLEEPOVA - 01/20/2023

-

Further Than The Furthest Thing - 01/20/2023

-

ON THE ROPES - 01/20/2023

-

THE WIFE OF WILLESDEN - 01/20/2023

-

Ain’t too proud - 01/20/2023

-

Standing at the Sky’s Edge - 01/11/2023

-

Botis Seva’s BLKDOG - 09/20/2022

-

BEST OF ENEMIES - 09/20/2022

-

BLUES FOR AN ALABAMA SKY - 09/20/2022

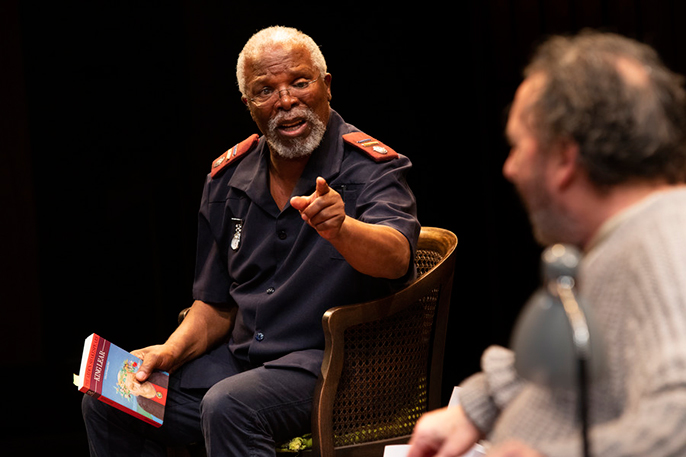

Dr John Kani – interview Kunene and the King Royal Shakespeare Company

With a career spanning over five decades, and multiple awards and accolades under his belt, Dr John Kani is a formidable force in the world of stage, screen and political activism. Originally from the Eastern Cape, he first came to global prominence at the height of South Africa’s apartheid era, when he co-wrote and starred in Sizwe Banzi Is Dead and The Island; winning (amongst others) a ‘Best Actor’ Tony award for the shows’ combined 1974 Broadway run. As a playwright, his work has often drawn from the viscerally racialised politics that afflict South African society – work that brought him into direct conflict with the apartheid regime’s most brutal enforcers. These days, he will be most familiar to many as King T’Chaka, father of the Black Panther in the Marvel Comic Universe and will soon lend his voice to the role of Rafiki in 2019 CGI remake of The Lion King.

Dr Kani is in the UK to premiere his latest work – Kunene and the King – a two-handed play in which he also stars alongside fellow South African theatre heavyweight, Antony Sher. Set in contemporary Johannesburg, the play tells the story of Lunga Kunene (Kani) and Jack Morris (Sher). Kunene – a black carer – is assigned to look after Morris – a white Shakespearean actor with terminal liver cancer – at Morris’ home in the suburbs. Both now in their 60s, the men are forced to confront the others’ experience of apartheid and post-apartheid in South Africa, twenty-five years after the declaration of the new ‘rainbow nation’.

I start by asking Dr Kani how easy it was – as both playwright and star – to hand over control of his work to director, Janice Honeyman.

“It’s difficult in the initial stages when you choose the director and the actor. [I was] very grateful that Tony Sher was excited to be part of this journey. And then during that process, of reading the words from a piece of paper for the first time, you are so nervous and protective as the writer. You want to hold on to each word, to each moment, to each situation. But then [with] the process of working on the text, unpacking the text, interrogating the writing – and I’m sitting there remembering my days when I used to be detained by the secret police when they would ask you questions! [Janice Honeyman] and Tony Sher would ask questions, ‘What do you mean here? What was the intention? What were you thinking about?’. It just reminds you of those interrogation days. But with these ones, I’m not going to end up in jail this evening, I can go home (laughs). So, it was wonderful. You hold on to some things, you let go of some things, you restructure, you revisit. The important thing is trust”. “[Janice Honeyman] has her whole heart in the welfare of the work – to make it much stronger and better. And of course, she’s also an actor’s director. So, she’s wonderful. Tony [Sher] is incredibly, brilliant in going right under the text and asking important questions. Being a South African who now lives in England, Antony Sher has not [lost] the memory of his childhood. He remembers the country very well and has been visiting quite periodically – his family’s still in Cape Town – so [it was good] to use an actor who has had an opportunity to step out, take a bird’s eye view, look at it, and go back into it”. “Tony Sher would come and say, ‘My God, you miss so much when you’re in there, you don’t see this’”.

It is in this uncompromising interrogation of South Africa’s ‘rainbow nation’ mask that Kunene and the King draws its most poignant scenes.

“What fascinated me,” Dr Kani explains, “is this fantastic façade in South Africa. I come from the township, I travel 15 to 20 kilometres, and we meet in our workplaces which are in the white citizen towns. We all meet there, we have a non-racial conversation, and we are the ‘rainbow nation’. But, at five in the afternoon, I go back to the township, and they stay in the white [areas]”. “I decided to keep [Kunene and Morris] in one room and see what would happen. I decided that Lunga Kunene doesn’t go home. He stays with Jack. And you test there this true democracy, this true non-racialism. What happens if they live together? And have to be in the same square metre and confront each other?”.

“They were in their late forties or fifties in 1994, so they still remember fifty years of apartheid. So, what is their attitude today when we celebrate 25 years of a democracy? What does the black man feel has been achieved, or still not achieved? [How has he been] let down? [What is he] disappointed in, or proud of? What does a white man feel has happened to his country, which was his alone before 1994; now in 2019, how does he feel? How does he judge South Africa today? Has he lost anything? Has he gained anything?”.

John Kani and Antony Sher in Kunene and the King – Photo by Ellie Kurttz (c) RSC

John Kani and Antony Sher in Kunene and the King – Photo by Ellie Kurttz (c) RSC

As an apparently liberal actor, much of the friction between the lead characters is fostered in Morris’ refusal to consider his own culpability in the injustices suffered by Kunene. I wonder the extent to which Dr Kani’s own experiences in the world of political activism and the arts have influenced the character.

“The thing that I wanted to thread through these two men was the fact that, as an actor, or an artist, or a painter, you are presumed liberal. So that’s why I made Jack Morris a Shakespearean actor. He says that it is a wonderful thing to work with black actors in movies, television and plays, but he’s never actually been with black people in the privacy of his home, in his own space. That was what I was trying to test”.

To Dr Kani, the relationship between South Africa’s siloed racially-homogenous communities and the cognitive dissonance towards the black South African experience is clear.

“South Africa is so wonderfully deceptive. There are still white areas, there are still black areas. You could live in Cape Town, Sea Point, next to the beach in Gordons Bay as a tourist and miss apartheid completely. Miss it, and then go back again into your own country and say, ‘I had a wonderful time in Cape Town!’ – and all you saw were the garden boys, the maids, and the people who work in hotels who serve you. You never met the people who matter, who are the character, and who define that country”.

The emotional impact of this structural indifference is palpable in Dr Kani’s portrayal of Kunene, as he challenges the extent to which Morris truly recognises his humanity – “When you look at me, what do you see? A nurse? A black man? But do you see me?”. As Dr Kani explains, “Before we become South Africans or Africans or whites or whatever you want to call yourself, we need to see each other first”.

Whilst Kunene and the King focuses its gaze on social cohesion in South Africa, I ask whether Dr Kani sees any parallels with racial politics globally.

“Art is universal at its most powerful moments. It speaks to the individual. The individual looks in the mirror and sees themselves in the content and context of the story being told. You can look to Brixton and see how far we’ve come since the 70s. You can look to Nottingham, to Liverpool, to Manchester. You look at the young black kids that are always ‘on spot checked’ for knives, ‘on spot checked’ for drugs, and feeling that they are the ones that are being targeted. You can look at the [football] match between England and Montenegro, with the racial slurs at black English players. I assumed these attitudes were associated with racism in my country, but I see it now even in [football] matches in England. We are all a ‘work in progress’ as far as racism is concerned. We all have attitudes which are motivated by our own inadequacies, our own shortcomings. Those are the issues I’m talking about”.

I put to Dr Kani that much of the current public discourse on racism revolves around the nuances of language and unpacking the more subtle indicators of unacknowledged prejudice in society – and ask what impact this might have on racial activism in the modern era.

“Today if you complain about a [racist] statement, even your own people call you reactionary, ‘You’re over-reacting, come on guys, can we move on now?’. When some white people say ‘You’ve got your freedom and empowerment, can’t we move on now? Can you leave us alone now?’. The language we use is very divisive. All I need to say is, ‘you people’, and immediately, immediately I’ve now divided the people. If I say ‘white people’, immediately I’m dividing the people, ‘You black people, you have a problem with white people’. The language we’re using needs to be reconsidered. We need to find the unifying language – a new English – a new language that would bring us together. That, for me, is the role of the arts, the role of theatre, the role of music, poetry and all. It is to listen – shut up and listen – and maybe you’ll learn something. Don’t talk while I’m talking! Listen, and I will listen when you speak. In that way, we may find each other”.

In an interview in 2014, Dr Kani described the arts in political activism as being like a “cultural AK47” that he could finally put away when apartheid ended; adding “I didn’t throw it away…put implies I know where it is…protest theatre will rise again”. Five years on, I ask him what he sees as the role of theatre in driving social and political change.

“As South Africa is today – as we watch the progress and take stock of what we’ve achieved – and what we’ve not achieved – theatre and art still have a critical role to play in the nurturing of our democracy; of a non-racial, non-sexist, emerging society and – most importantly – the upliftment of people. In the arts, especially theatre, we find the voice of the repressed is being heard much louder. Those voices come out now much stronger and there is a place where they can be heard”. “We can do comedies, but they will always be informed by who we are, and where we are, and what’s going on around us – the environment”.

John Kani and Antony Sher in Kunene and the King – Photo by Ellie Kurttz (c) RSC

John Kani and Antony Sher in Kunene and the King – Photo by Ellie Kurttz (c) RSC

In recent years there has been an increased focus on improving minority representation in the arts, particularly in the world of Hollywood. This has, of course, not been without its controversies – with the ‘Best Picture’ Oscar for Green Book being a notable recent example of acclaim for films that impose a ‘white saviour’ narrative to stories of black achievement. As one of the predominantly black cast of the critically acclaimed and commercially successful Black Panther film in 2018, I ask Dr Kani for his opinion on the state of minority representation in the world of cinema.

“Who holds the purse, plays the music – and we dance. Until black people – black billionaires, black millionaires – find the need, the importance of investing in the arts, the work of Africans will always be a secondary consideration in the Hollywood blockbuster industry”. “What was wonderful about Black Panther was that it was almost an all-black company, an all-black cast on stage. [Director] Ryan Coogler used a given opportunity to say a little bit more than just a crime-fighting universal life-saving international boy from America that’s going to solve the problems of everybody wherever they are. Black Panther proved that an all African and African-American cast can do a movie, a blockbuster, that could gross over 1.2 billion, which gives the Hollywood investor confidence to invest in the next one”.

“[The idea of this] imaginary country of Wakanda being somewhere in Africa, a country that was never colonised, for me was incredible because it answered the old age question, ‘Would Africa have developed to the present level of the global community had it not been colonised?’. There was an example of a country that was never colonised – imaginary, I grant – but it was never colonised – [and was] technologically advanced more than anything in the world. And that would then give my young grandson [the chance to] look at the screen and see a hero who is black and looks like him. For that one moment, that little black child can say, ‘I can be him, I am a hero too, I am somebody’…But then they do the next movie, and the next movie (laughs) and the next movie… so please don’t attach too much [importance] on these things because it’s an industry”. “What was also pleasing for me was being allowed to use an indigenous African dialect (Dr Kani’s native IsiXhosa was used as the indigenous language of Wakanda).

So, in that sense, when it played in South Africa and in Africa, the people could identify the dialect. They were not doing the Tarzan language, ‘ungabunga-ungabunga’, with subtitles ‘How are you?’ (laughs) you know, making it up. At least we were given the opportunity to use the language. And everybody there, from Forrest Whittaker, Angela Basset, Lupita N’yongo, Danai Gurira, everybody on set, were saying ‘Help me Doc, can you just, give me a line, what can I say here? I would like to say something’. So that was the beautiful experience I had”.

Kunene and The King is showing at The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until 23rd April

This is Lime 2020